- Revenue Cycle Management

- COVID-19

- Reimbursement

- Diabetes Awareness Month

- Risk Management

- Patient Retention

- Staffing

- Medical Economics® 100th Anniversary

- Coding and documentation

- Business of Endocrinology

- Telehealth

- Physicians Financial News

- Cybersecurity

- Cardiovascular Clinical Consult

- Locum Tenens, brought to you by LocumLife®

- Weight Management

- Business of Women's Health

- Practice Efficiency

- Finance and Wealth

- EHRs

- Remote Patient Monitoring

- Sponsored Webinars

- Medical Technology

- Billing and collections

- Acute Pain Management

- Exclusive Content

- Value-based Care

- Business of Pediatrics

- Concierge Medicine 2.0 by Castle Connolly Private Health Partners

- Practice Growth

- Concierge Medicine

- Business of Cardiology

- Implementing the Topcon Ocular Telehealth Platform

- Malpractice

- Influenza

- Sexual Health

- Chronic Conditions

- Technology

- Legal and Policy

- Money

- Opinion

- Vaccines

- Practice Management

- Patient Relations

- Careers

Caring for the uninsured: Will the problem ever be solved?

As the numbers climb, people from opposing camps begin the search for consensus.

Cover Story: Caring for the Uninsured

Will the problem ever be solved?

As the numbers climb, people from opposing camps beginthe search for consensus.

By Anne L. Finger, Senior Editor

(Above) FP Joseph A. Babbitt speaks with patient Wendell Davis inDeer Isle, ME.

When former AMA president Nancy Dickey toured the country last year tosound an alarm about the growing problem of America's uninsured, she wasmet by a uniform hitting of the "snooze button." Even four yearsafter the defeat of the Clinton plan in 1994, it seemed, the nation wassuffering from health policy fatigue.

But suddenly, people have stopped dozing. With more than 16 percent ofthe US population lacking health insurance, the issue can no longer be ignored.Individual physicians, of course, have never ignored the uninsuredbecauseof both their sense of moral obligation and their position in the frontlines. Now, there are clear signs that the rest of society is also beginningto wake up to the problem.

In June, seven physician groups, including the AMA, launched a campaignto make universal health care coverage the No. 1 priority in the 2000 presidentialelection. In October, newspapers trumpeted the Census Bureau's report thatthe number of uninsured topped 44 million in 1998, an increase of nearly1 million over the previous year. Vice President Al Gore introduced a programto reduce that overall number, and former Senator and presidential aspirantBill Bradley one-upped him with a more ambitious proposal to provide coveragefor 95 percent of the uninsured. And policymakers have a newfound eagernessto tackle a trio of health care concerns: about the uninsured, Medicare'sfuture, and HMO liability.

It's not a moment too soon. Despite economic prosperity and low unemploymentrates, the employer-based system of health coverage is showing signs ofwear. More workers are employed in part-time and temporary positions andmore are changing jobs, making coverage less available and more costly.This is the case despite COBRA and the Health Insurance Portability andAccountability Act, which were intended to ease the burden for job changers.

With the rising costs of health care, fewer employers in small companiesare offering coverage.

Many of those companies that do still offer coverage are asking employeesto pay some or all of the premiums. So millions of workers who are citedas having coverage from their employers actually pay the entire premiumthemselves.

And premiums are rising once again, hitting small businesses the hardest.Every year since 1986, members of the National Federation of IndependentBusiness have reported that the rising cost of health insurance is theirNo. 1 problem.

Adding to the strain, Medicaid has recently ceased to cover many of thepoor. An additional 675,000 low-income people have become uninsured sincelosing their Medicaid coverage with the implementation of welfare reformin 1997, according to a report by Families USA. Many of these peoplethemajority of whom are childrenare probably still eligible for Medicaid,but they don't realize it, or they're hopelessly tangled in red tape.

So it's time to ask some questions: What's been causing this decade-longtrend that's seen the ranks of the uninsured swell by more than 11 million?Who are these people? How are they affected by their lack of insurance?How likely are we to form the national consensus necessary to remedy theproblem? And what form might that remedy take?

The uninsured may not be who you think they are

There's a perception that most of the uninsured either are temporarilywithout coverage because they're between jobs or are moochers who chooseto get by without insuranceuntil they're very sick, that is, when theygo to a hospital ER and receive excellent charity care.

By most accounts, though, those two categories are a small proportionof the total. The majority of the uninsured are simply low-income peoplewho have difficulty affording the premiums, says Peter Cunningham, seniorresearcher with the Center for Studying Health System Change. Accordingto the 1999 Census Bureau report, roughly one-third of both the poor andnear-poor (those with family income either below the poverty level or nomore than 125 percent above it) lacked health insurance in 1998, whereasonly 8 percent of those with annual incomes of $75,000 or more were uninsured.

In a recent study, Cunningham and his colleagues found that about 20percent of the nation's uninsured had declined insurance offered to themeither at their workplace or by a family member's employer. Two-thirds ofall uninsured workers and three-fourths of the low-income uninsured gavecost as the reason. "We also found that low-income workers are oftenrequired to pay a larger amount than higher-income workers," says Cunningham.In firms where the typical wage is less than $7 an hour, family coveragefor the most inexpensive plan averaged $130 a month, compared with $84 amonth for family coverage in firms where the typical wage is more than $15an hour. "There's no question that cost is a barrier," he says.

The fact that the poor pay more was also confirmed by a 1997 CommonwealthFund study. A person at the poverty level would need to spend 32 percentof income to buy health insurance on the open market, the study found, andin some areas a family of four at the poverty level would have to devoteas much as 46 percent of income. It's hardly surprising that many of thesefamilies decline coverage. According to economists, fewer people retaininsurance when premiums surpass even 10 percent of their family's income.

Of the nearly 60 percent of the uninsured who were from low-income familiesin 1997, a Kaiser Commission study found, one-third are children, one-thirdare parents or other adults caring for children, and one-third are adultswith no children. Many are young men, who usually don't qualify for Medicaidbecause they're not single parents. Among ethnic groups, Hispanics are mostlikely to be uninsured.

The low-income uninsured are, for the most part, working people employedin businesses of fewer than 100 employees. About 80 percent live in householdsheaded by a working person, and about 64 percent work full time. Ironically,low-income workers are less likely to be insured than low-income nonworkers.

"This is not a difficult issue to understand," says RobertBlendon of the Harvard School of Public Health. "The uninsured areprincipally working people earning between $18,000 and $25,000 a year. Afamily policy sells for $400 to $500 a month. They can't pay that."

Another prominent segment of the uninsured is people 18 to 24, the so-calledGen Y. This is the population that's at the highest risk for accidents involvingtraumatic brain injuries and possible long-term disability, points out aFebruary 1999 article in American Demographics. Says FP Charles DavantIII of Blowing Rock, NC: "I can shed a lot of tears for a few of theuninsured. But in my experience, the majority are younger and healthierthan average. They drink alcohol, ride motorcycles, smoke too much, andignore preventive services. They make bad choices."

But the decision of young people to "wing it" without insuranceisn't always cavalier. Workers under 25 were less likely to be offered healthinsurance in 1996 than they were in 1987. What's more, the cost of premiumsrose by 90 percent between 1987 and 1993, far higher than wages did. Priceis clearly a factor when young workers are offered insurance but turn itdown.

How does lack of insurance affect health careand health?

Many Americans believe that anyone who needs health care can get it.But numerous studies suggest that, compared with an insured population,the uninsured are more likely to delay seeking care, have higher hospitalrates for health problems that normally don't require hospitalization (diabetes,hypertension, immunizable diseases), are less likely to receive surgeryfor hip replacement or coronary bypass, are more likely to die of breastcancer, and generally have higher mortality than those with insurance.

A 1996 Kaiser Family Foundation study on the uninsured concluded: "Thesickest people surveyed are most likely to have problems getting the medicalcare they need. The vast majority of uninsured adults in poor health haddifficulty getting care. This finding directly contradicts the conventionalwisdom that truly sick people can always get care when they need it."

And The Commonwealth Fund 1999 National Survey of Workers' Health Insurancereported "disturbingly high numbers of uninsured people who do nothave the resources to pay medical bills and who live in insecurity abouttheir health and finances." In the past year, one of four adults reportedgoing without needed medical care when sick because of costs.

Physicians treating the uninsured also make decisions based on cost,reports The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. They elect not to use certainexpensive diagnostic tests or the most effective drugs, and they're lesslikely to refer to specialists or recommend invasive procedures.

Although most Americans would be offended by the concept, it's clearthat both physicians and patients are rationing. "The truth is,"says FP Joseph A. Babbitt from Deer Isle, ME, "we say No every day.We're already rationing care. We just ration it in an arbitrary manner."

Blendon, who has done a number of surveys of the uninsured, says physicianssometimes have misperceptions about who the uninsured are and what kindof care they get in ERs: "Doctors don't recognize that a lot of peopledon't fill prescriptions or come back for visits because they're too proudto take charity care."

The states try to take up the slack

When federal health policy seemed to be going nowhere, there was actionamong "the states that couldn't wait," says Laura Tobler, seniorpolicy specialist at the National Conference of State Legislatures. Theapproaches varied, with the most notable being Oregon's Medicaid expansionprogram, which moved rationing out of the closet; Hawaii's statewide employermandate; and TennCare, Tennessee's self-imposed removal from Medicaid to a broader systemof health insurance.

The big news lately on the state level is S-CHIPthe State Children'sHealth Insurance Program. In 1997, Congress, unable even to consider a comprehensivenational health program, enacted a way to encourage health care for kidsunder 19. The program is aimed at children whose family income is at orbelow 200 percent of the poverty linethose who would otherwise fall throughthe cracks between Medicaid eligibility and private insurance. Congressallocated more than $20 billion for a five-year matching program with thestates, with additional funding after that. States could use the funds toexpand Medicaid, develop a new CHIP program, or do both. In addition, somestates are dedicating the money from tobacco settlements for CHIP.

Despite these innovations, the combined resources of Medicaid and CHIPcovered fewer children in 1999 than Medicaid alone covered in 1996, reportsa Families USA study. Examining the 12 states that account for nearly two-thirdsof all uninsured, the report found that CHIP enrollment reached 920,796,but Medicaid declines of nearly 1 million erased the gains.

This is less an indictment of CHIP, which is still in the formative stages,than a warning about Medicaid. Says Nancy Dickey: "We believe thatabout half the uninsured children probably qualify for Medicaid but havenot applied for it, usually because of bureaucratic barriers or becausetheir immigrant parents are fearful of getting into the system. Californiahas about a 28-page application. Iowa used to make you reapply every month.In my state, Texas, you have to actually go to the department of human services,and Texas isn't known for its public transportation. We make a promise tocover the poor, but sometimes we appear to go out of our way so we don'thave to deliver on that promise."

American Academy of Pediatrics President Joel Alpert spoke of those barriersandmorein his address at the AAP's annual meeting in October. In additionto barriers of race, language, culture, and geography, he said: "Medicaidand S-CHIP require ongoing means testing. Our country has more than 50 programswith different eligibility standards and enrollment procedures," meaningthat someone who moves to a new state has to learn all new rules. "Allthis is why we find millions of children who are uninsured, despite beingeligible for Medicaid or S-CHIP."

Physicians who know a patient is uninsured can help by directing herto a Medicaid office, says Ron Pollack, president of Families USA. "Theprimary care doctor can be instrumental in making sure people get what they'reentitled to."

But even improving access to Medicaid may not be enough. "A lotof people want nothing to do with government," says Vondie Woodbury,project director of the Muskegon (MI) Community Health Project. "Itbecomes a barrier to people seeking care." Her community's innovativeprogram subsidizes both the employer and the employee.

To Victoria Caldeira, manager of legislative affairs at the NationalFederation of Independent Business, the fact that the uninsured are increasingis evidence that state reforms aren't working. "The more highly regulatedthe states are, the more uninsured they have," she says. Although theNational Conference of State Legislatures has found no correlation betweenthe number of state-mandated benefits and the size of the uninsured population,the indisputable rise in the numbers of uninsured underscores that stateshave not resolved the problem.

A new millennium, and a new search for consensus

Perhaps this latest round of attention will begin to resolve the problem.Harvard's Robert Blendon suggests why the plight of the uninsured is nowback in the public eye. In the past, he says, political discussions of theuninsured were invariably combined with cost containment, which raised thespecter of government control. When those two topics are linked, he continues,"you lose many groups, because the people who want cost containmentare usually not the same people who want to help the uninsured." Doctorsand hospitals, he points out, would support a plan to help the uninsuredthat didn't impinge upon their own fees, salaries, or budgets.

What came to the rescue? "Managed carefor better or worsebecamethe cost containment issue," Blendon says. "So instead of discussinggovernment's controlling cost, we're just discussing ways of encouragingthe uninsured to get insurance. That has made this issue politically easierto deal with."

Indeed, a national public opinion survey released in October indicatesthat people are ready to deal with the problem. Just about as many respondentsfelt a budget surplus should be applied to helping the uninsured get insuranceas to preserving the financial health of Social Security and Medicare. Ninetypercent said they favor making sure all families and children have accessto affordable health insurance coverage, and 69 percent said they're willingto spend as much as $50 per year in new taxes to ensure that Americans getcoverage.

"There's a big consensus that something needs to be done,"agrees Peter Cunningham of the Center for Studying Health System Change,"but no consensus at all on how to do it." He's not convincedthat government's role will grow large any time soon. The fear of universalcoverage among parts of the population is based on fear of government-controlledhealth care, he says. A single-payer system, which some economists believeis the most sensible approach administratively, may receive serious considerationat some point. But few people think now is the time.

The most talked-about proposals are variations of two basic plans: reupholsteredemployer-based systems, or tax subsidies and incentives to move toward individualizedinsurance. Both alternatives are usually joined by expanded coverage ofthe government safety net. Since the defeat of the Clinton plan, "incrementalchange" has become the byword.

But incremental change sometimes leads to unintended consequences. TheCHIP program has led to concerns about "crowd-out"the movementof individuals and employers out of private insurance and into the governmentprogram. Medical savings accounts have been criticized for fostering adverseselection: Only relatively healthy people buy the policies, leaving thesickest unprotected. The Patients' Rights bill has been faulted for potentiallyraising the price of coverage.

Still, there are hopeful signs of a budding consensus. One such signis the group of 50 leaders that participated in an annual forum called theHealth Sector Assembly, convened by the AMA and several pharmaceutical companies,representatives from physician and other health care groups; government,business, and consumer organizations; the insurance industry; and academia.Participants agreed to a statement of broad principles for achieving universalhealth care coverage. "The fact that . . . approximately one in sevenpeople do not have health care coverage threatens their health and is bothan embarrassment to our nation and a barrier to our future success,"stated a preamble to the seven principles. The principles establish thehealth of the American people as a "national asset" for whichthere is a "moral imperative" to invest wisely. They speak ofthe need for a "uniquely American solution," which will be "achievedthrough a series of steps" and will encompass "a pluralistic blendof public and private sector elements."

Another positive sign is an upcoming conference, sponsored by The RobertWood Johnson Foundation, that will bring together representatives of business,health, consumer, and labor groups. Co-sponsors include the Health InsuranceAssociation of America and Families USA, longtime rivals in the nationalhealth care debate. Both groups will present concrete proposals at "HealthCoverage 2000: Meeting the Challenge of the Uninsured," which willbe held in Washington, DC, next month. So will the AMA, the American HospitalAssociation, the American Nurses Association, the Service Employees InternationalUnion, and the US Chamber of Commerce. HIAA has already announced its proposal;Families USA hadn't before our press date.

Both HIAA and Families USA will advocate building on the employer-basedsystem. "The employer-based system is clearly threatened from a lotof angles," says Chip Kahn, executive director of HIAA. "But youneed group purchasing, and your groups have to be organized around a reasonother than their health status." Says Families USA's Ron Pollack, "Iwouldn't have chosen the employer-based system, but if we're tearing somethingdown, we should know we have something better to put in its place."He expresses concern that an individual-based system would increase discriminationagainst those who are sick.

Both groups also advocate expanding coverage of Medicaid and CHIP. "Ourconclusion is that most of the uninsured lack the wherewithal to obtaininsurance," says Kahn. "Insurance companies can't mint money,so it will have to come from the government and taxpayers." Pollacksays, "Our only relatively recent incremental improvement was in CHIP,and I think that occurred because none of the major special interest groupsfelt their ox was being gored. That's instructive: We need to build on whathas worked."

Based on several surveys he's done over the years, Blendon stresses thata subsidized plan must not look like a charity welfare plan. "Manyof the uninsured have never taken charity in their lives," he says."They won't stand in line at a charity hospital unless they're terriblysick and desperate. But a very large share say that if there were subsidies,they would, in fact, take the coverage."

Questions remain, of course, about the source of the funds. "Moneyfrom the surplus or a possible federal tobacco settlement would be verypopular with the public," Ron Pollack says.

Clearly, this is an optimum economy for attempting to resolve the problem."What in heaven's name will happen during a recession?" askedSen. Jay Rockefeller of West Virginia at a Washington symposium.

What indeed? The National Coalition on Health Care projects that if therewere an economic downturn while prices continued to rise, an additional17 million people would be uninsured a decade from nowmeaning that nearlyone in four non-elderly Americans would lack health coverage. Some expertspredict that even if our unprecedented prosperity continues, up to 54 millionpeople could be uninsured in the year 2007.

"It's possible," says Cunningham, "that nothing will getdone until the problem starts touching the middle class. If the economygoes sour, and we see people laid off or premiums rising beyond what middle-classpeople can afford, the issue may reach such political salience that politicianshave to do something significant. I think the problem may get worse beforea strong consensus can be achieved on how to fix it."

Blendon, however, expresses optimism, and stresses the vital role physicianscan play. "It's very important for doctors to know that this canvasisn't painted yet," he says. "The patients' rights bill passedthe House because physicians combined with people who were angry. If physicianshadn't been well-organized and angry themselves, it never would have happened.

"If they get really involved and passionately care about gettingthis done, we can see 20 to 30 million people covered in the next five years.But first, you have to win a political battle about the direction to takeon this issue. There's clearly a growing interest in the uninsured, butthe problem could just sit there unless a lot of professional groups decidethey want to take this issue seriously. If they do, something could reallyhappen."

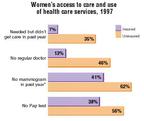

How lack of insurance affects women's health

Nearly one in five women between the ages of 19 and 64 has no healthinsurance, and the percentage is highest (23.4 percent) among women youngerthan 35. The impact on care? A Kaiser Family Foundation survey found thatwhereas 84 percent of women with private insurance reported having had aroutine gynecological exam in the past year, only 59 percent of uninsuredwomen reported receiving one. Here are some other findings from the KaiserFamily Foundation.

*Mammograms were measured for women 50 years of age or older.

Source: Kaiser/Commonwealth 1997 National Survey of Health Insurance

A community forges a strategy

Beset by rising numbers of uninsured residents and businesses unableto pay for employees' health insurance, Muskegon County, MI (pop. 168,748),accepted a challenge from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation to come up with aplan. (The nonprofit foundation is seeking "local visionary models"of health care for the underserved.) For four years, the county's businessleaders, physicians and other health care providers, and community groupsparticipating in the Muskegon Community Health Project held meetings andsurveyed the population. Earlier this year, they introduced Access Health,a community-engineered and -sponsored solution to the problem of the uninsured.

On Sept. 1, the first Muskegon residentsall full- or part-time employeesof local businesses, not eligible for Medicaid, and not covered by a spouse'splanwere enrolled in Access Health. They were selected on a first-come,first-served basis after an extensive community-wide media campaign. Theorganizers anticipate 3,000 members and an additional 1,000 dependents.The number has been limited in this initial stage to what the organizersfelt was a manageable group to treat and collect data on for the future.The group represents about 25 percent of Muskegon's uninsured.

"This is health coverage," says Vondie Woodbury, project directorof MCHP, "not health insurance." Rejected by six HMOs wary ofthe risk involved, the community is self-insuring. Claims settlements, billings,and collections are being handled by two third-party administrators.

The basic benefits package covers care from any of the community's 200primary care physicians and specialists, as well as charges for lab andX-ray, generic medicine, emergency room, inpatient care at either of thetwo hospitals, home health care, and hospice. To limit risk, the plan excludescare outside Muskegon, neonatal care, severe burns, transplants, and limbreattachments.

The focus at this initial stage is on employees of businesses with fewerthan 20 people and a median wage of less than $10 an hour. The businessesmust not have provided health insurance for at least 12 months. Employersand employees each pay about $38 a month, which represents 60 percent ofthe total premium. The balance comes from a community fund financed by contributionsfrom businesses, individuals, and federal matching funds. The total $122premium is comparable to the market rate; the advantage here, of course,is that it's shared.

Doctors are paid Medicare fee-for-service rates plus 10 percent, butthey donate 10 percent to Access Health to administer the system. They alsoagreed to bear the risk. "Our providers have been at risk with thispopulation," Woodbury says. "Now, we're providing a level of reimbursementthat's much better than what they had been getting."

Access Health has ambitious plans. "We hope to create a concurrenteducation component for members," says Woodbury. "We're workingwith folks at Michigan State University on how to do that; home visits willbe a part of it. We'd also like to bring the businesses together for worksitewellness programs."

But with health care costs rising, the project faces a large self-imposedchallenge: In order to assuage employer/ employee anxiety that the premiumswould continue to rise, it has vowed to freeze premiums and copays for threeyears.

. Caring for the uninsured: Will the problem ever be solved?.

Medical Economics

1999;24:132.