Article

Medical ethics: Patients' needs versus maximizing income

Physicians must put patients first, but you also need to be profitable. Here's how doctors tackle the wrenching decisions about money and ethics.

But it's also a way to make a living, and as such, doctors are faced with many of the same enticements as other professionals. Chief among them is the temptation to maximize income, or at least to bring in enough cash to repay medical school debts, keep a practice afloat, and pay for life's necessities and a few luxuries.

There are times, though, when the quest for income bumps up against the ethical stricture that physicians should put patients' needs above all else. And that clash has become more pronounced as doctors' incomes have stagnated in the wake of third-party payer cutbacks and a looming recession.

Among the economic challenges that test today's physicians' ethical fiber, in addition to whether to accept Medicare and Medicaid patients in light of declining compensation, are the temptation to undertreat patients to keep costs down or overtreat patients to boost practice income; making treatment decisions involving frail elderly, terminally ill, or underinsured patients; and dealing with noncompliant patients who might compromise doctors' pay-for-performance (P4P) ratings. Here's a look at these issues, along with suggestions from medical ethicists and physicians in the trenches on the least harmful ways to resolve them.

Less money from your Medicare patients

Primary care physicians may be more prone than specialists to make decisions based on payment method, because PCPs are less well-compensated and generally have steeper overhead expenses than specialists, says Frederick Turton.

That combination of high overhead and low reimbursement is often the critical factor in physicians' decisions to close their practices to Medicare and Medicaid recipients-an issue that took on new urgency this January, when changes were slated to go into effect that would have decreased Medicare payments by 40 percent over nine years. Congress ultimately stepped in to block the proposed cuts, and even boosted Medicare reimbursement by 0.5 percent beginning Jan. 1. But that paltry increase expires on June 30, meaning that payment reductions will begin in July unless lawmakers approve another bill to hold rates steady.

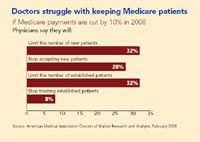

If Congress demurs this time, the number of physicians who won't take on new Medicare patients is likely to jump, and some doctors would even cut established Medicare patients from their rosters. When the AMA polled its members in 2007, 60 percent of respondents said that the planned cuts would induce them to limit the number of new Medicare patients they see. (For more details, see the chart.)

Naperville, IL, family physician Elizabeth A. Pector, for one, will only take new Medicare patients if they're immediate family members of established patients. And FP Patricia F. Hollingsworth of Columbus, OH, says that if Medicare follows through with reimbursement cuts, her practice would stop seeing new Medicare patients and potentially dismiss current Medicare patients in order to remain solvent.

Internist Cecil Wilson, immediate past chair of the AMA board of trustees, sees the issue of deselecting patients on the basis of their insurance carrier (or lack of one) as less a matter of ethics than of physicians making painful choices in order to stay in business. "It's not that physicians don't want to take care of Medicaid and Medicare patients," Wilson says. "The reality is that many physicians are small businessmen. We have to turn on the lights, hire staff, buy equipment, invest in information technology, and so forth. Any business facing sharp income reductions has to decide how to remain financially viable."