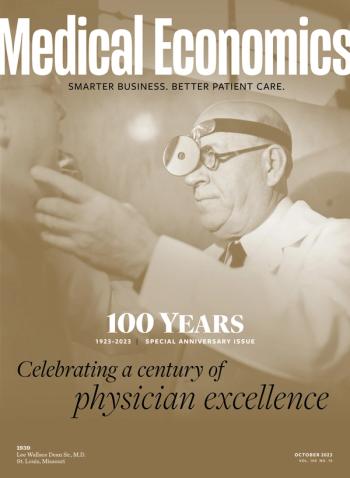

- Medical Economics October 2023

- Volume 100

- Issue 10

How modern medicine was made, part 4: The importance of insulin's discovery

'The rational treatment of disease.'

Physicians in 1923 would have remembered startling news from just a year before: A newly discovered substance called insulin could revive children with diabetes on their deathbeds.

Diabetes has been known for centuries, recognizably described by healers of ancient Egypt and Greece. They says it was relatively rare, but always deadly. Historically, physicians tried to cure it or manage it with various diets, or sometimes no food at all. They succeeded only in delaying the inevitable as patients’ bodies withered.

In January 1922, Leonard Thompson, 14, was the first patient with diabetes to receive a healing dose of insulin while hospitalized in Toronto. Tales of his recovery, and of others like him, send shivers up your spine, says John B. Buse, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Diabetes Care Center at the University of North Carolina.

“They would give them a shot of insulin and these kids would perk up in hours. I mean, it was a miracle,” Buse says. “So, insulin isn’t a cure for diabetes, but it turns something from a uniformly fatal and very rapidly progressing disease to one that, with good care, can result in nearly normal life expectancies, even 100 years ago.”

He noted some of those earliest patients would outlive physician Frederick Grant Banting and physiology student Charles Best, the Canadian scientists whose earliest insulin solution was made from ground pancreases of dogs.

By April 1922, Eli Lilly and Company proposed large-scale purification of insulin. New formulations, generally derived from cows and pigs, would follow in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. Those could cause immune reactions in patients but were close enough to human hormones to work wonders, even if much of it was guesswork for decades.

“Insulin obviously was a game changer, but we didn’t have the ability to use it with much precision,” says Thomas W. Martens, M.D., medical director of the International Diabetes Center at Park Nicollet Clinic and HealthPartners Care Group in Minneapolis. “You’re basically just injecting an insulin extract into your subcutaneous tissue. There wasn’t much precision in dosing. There wasn’t really any good way to be able to monitor it.”

“Things got better a little bit,” says Bill Russell, M.D., of the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tennessee. “I’m showing my age here, but I did my training in the mid-’70s, and management of diabetes in that era was little changed from the 1920s.”

Buse noted two additional developments that were crucial for modern diabetes research. Blood glucose meters, developed in the 1960s by Anton H. “Tom” Clemens, entered the market in the early 1970s.

In 1978, Genentech and City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California, announced successful laboratory production of human insulin using recombinant DNA technology. It became the first genetically manufactured drug to earn FDA approval and was part of a long line of research to develop long- and short-acting insulin formulations.

Congress passed the 1974 National Diabetes Mellitus Research and Education Act acknowledging “diabetes mellitus is a family of diseases that has an impact on virtually all biological systems of the human body.”

The law directed the National Institutes of Health to mobilize with new regional study centers; a year later, the new National Commission on Diabetes recommended a five-year clinical study of the effects of Type 1 diabetes. That long-term study, the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT), happened in 1983, with 1,441 people with Type 1 diabetes participating. They measured control through the hemoglobin A1C test developed by Anthony Cerami, Ph.D., funded by Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation in the 1970s.

After 10 years, JDRF stated the results were clear: Participants who kept their blood glucose levels as close to normal as possible reduced risk of eye disease by 76%, nerve disease by 60%, and kidney disease by 50%.

In the 1990s, the DCCT and other studies launched diabetes research into “warp speed — we need better insulins, we need better ways to inject insulin, we need better ways to deliver insulin, we need better ways to understand the whole process,” Russell says. The findings inspired new efforts to resize and refine glucose meters and insulin pumps, invented in the 1960s and marketed commercially starting in 1979.

Medical knowledge grew about the “family of diseases.” Researchers began to understand that Type 1 diabetes, which often developed in children, could happen in adults.

Historically, some adults who did not have diabetes as children developed conditions like diabetes later in life. That condition also had existed since ancient times; French researchers differentiated between two types of diabetes in the 19th century, and the British physician Harold Himsworth in 1936 postulated about a condition, insulin resistance, distinct from insulin deficiency. In 1979, the National Diabetes Data Group of NIH formalized the distinction between Type 1 diabetes, formerly known as juvenile diabetes, and Type 2 diabetes, formerly considered adult-onset diabetes.

Physicians and patients know more about the role of the pancreas and insulin. No one yet knows exactly why the body shuts down its ability to make it.

Pancreas transplantation is possible and could be a “cure” for some patients. But like any organ transplant, it has risks and complications, the donor supply is far too small for widespread use and there is no guarantee the patient’s immune system will not shut down the new pancreas, the experts says.

Now researchers hope to connect and perfect closed-loop systems of continuous glucose monitors and pumps that deliver insulin as needed in real time. Or modify stem cells to be implanted to jump-start the pancreas’ ability to make insulin. Or figure out how to stop diabetes from happening in the first place.

The discovery of insulin also advanced medical cause and effect, says Mitchell A. Lazar, M.D., Ph.D., founding director of the Institute for Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine. “There really were not that many rational treatments of diseases in the early 1920s, when insulin was discovered,” Lazar says. “Up until then most of the medical therapies were sort of quack therapies, bloodletting and special kinds of baths and so on, that really weren’t of any true medical benefit. But insulin was the actual thing that was missing and could be replaced in this devastating disease. It just has so much historic importance for that reason.”

Lazar predicted physicians and patients 100 years from now will be talking about “breakthrough discovery science that we can’t even imagine yet.” He says, “We’re talking about stem cells and recombinant DNA and closed-loop pumps that Banting and Best, who discovered insulin 100 years ago, wouldn’t even have imagined.”

How modern medicine was made: Table of contents

Introduction Part 1: The importance of medical imaging Part 2: The power of vaccination Part 3: The history of antibiotic development Part 4: The importance of insulin's discovery Part 5: The development of surgery and organ transplantation Part 6: Military medicine advances health care for soldiers and civilians Conclusion: Improving lives

Articles in this issue

over 2 years ago

The future of medicine - what patients expectover 2 years ago

The doctors bag in 2023over 2 years ago

The doctor's bag in 1923over 2 years ago

A century of primary care transformationNewsletter

Stay informed and empowered with Medical Economics enewsletter, delivering expert insights, financial strategies, practice management tips and technology trends — tailored for today’s physicians.