Article

What would you do? "Doc, can you write me a note?"

Author(s):

In an earlier issue, we told you about a patient who wanted a note to get out of work. Here's what you told us you'd do.

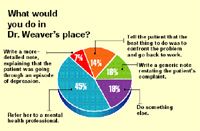

In our Aug. 20, 2004 issue, internist Stephanie L. Weaver told you about the difficulty she'd had in deciding what to do when a patient who'd been experiencing job-related stress asked Weaver for a note to take time off from work. (See "Doc, can you write me a note?" Aug. 20, 2004 http://www.memag.com/memag/article/articleDetail.jsp?id=115527). We ended Weaver's story without telling you how she dealt with Jane M.; instead, we asked what you would do in the same situation. Would you tell the patient to confront her problem and go back to work? Write a generic note restating the patient's complaint? Write a more-detailed note, explaining that the patient was going through an episode of depression? Refer her to a mental health professional? Or find another solution?

In the end, Weaver's choice was to refer Jane to a mental health professional. Here's what she told the patient: "You seem to be overwhelmed by your current situation. When situations that we can't change overwhelm us and make us feel helpless, that often leads to depression and a stress response that can adversely affect our health. The best thing to do is to change your response to the situation, but that's hard to do on your own. I want to refer you to Dr. Jones, a mental health specialist, and she can help us figure out how long you might need to be off work and help you work on coping skills that could help you feel less stressed."

The biggest portion of our readers-45 percent-agreed with Weaver, saying they'd refer the patient to a mental health professional. Of the rest, 14 percent would tell the patient to go back to work, 16 percent would write a generic excuse restating the patient's complaint, 7 percent would write a more-detailed note, and 18 percent would do something else. (The latter category included prescribing antidepressants or sleeping pills, and recommending exercise.)

If you are willing to write a note for the patient, said GP Leopoldo D. Villaneuva of Pensacola, FL, request only a short time off. "Give her an excuse until she can be seen by a mental health professional. Then let that person decide when she can return to work or recommend that she change jobs."

"I would have told the patient I'd give her a note recommending time off and identifying a reason for being off-specifically, stress," said FP John J. Messmer III, associate professor of family and community medicine at Penn State College of Medicine, and Medical Director of the University Physi-cian Group in Palmyra, PA. "But I'd require her to work with me over the period she had off-say, two weeks-to identify ways of managing the stress. If that weren't possible, we'd try to identify another option, including changing jobs or seeking legal action.

"If she did not agree to work with me, I'd tell her I could only give her a note for a day or two until she sought help through a mental health professional. Mental health is like any other health problem. If she hurt her back and refused to return or do my prescribed treatment, I would limit the recommended time off. Time off is for treatment, not vacation."

Other readers would handle the patient's condition differently. "I would put her on an SSRI or refer her to a psychiatrist," said GP Kermit Till of Brandon, MS. "She just needs to be on the proper medication and go to work."

Primary care doctors shouldn't have to deal with these issues at all, said another physician who preferred to remain anonymous. "Weaver should refer this patient back to her human resources department to file workers' compensation paperwork for her 'work-related stress' claim. The patient can be evaluated by a workers'-comp physician and be referred to a mental health professional. The Family and Medical Leave Act is not designed to take the place of workers' compensation benefits."

Other respondents take the middle ground. One physician who has used the approach of restating the patient's complaint in a note said he always explains that the employer is likely to ask for more information. "I have the patient come in again if a long, multipage form appears.

"It helps to set limits, and to help the patient understand that a little time off is not the answer. I would also encourage her to look at other options, including job change if this is likely to be a long-term issue. If a patient requests disability (the next logical step for some employees), I generally refer to a specialist."

FP Keith W. Stampher of Colorado Springs also likes the idea of writing a generic excuse. "It works in almost all situations and is always the most effective move." But, in addition, he'd try to work with the patient on her underlying problem, referring her to a counselor if needed.

Stampher cautioned that writing a detailed note can get a doctor in trouble. "Providing psychiatric details to an employer is a clear violation of the patient's privacy at this point in the evaluation process, especially if the provider isn't comfortable with psychiatric labels or diagnoses."

The idea of telling the patient to stand up for herself at work or change jobs (perhaps within the same company) came up several times. Internist Christopher S. Westra, associate medical director of Kimberly-Clark Health Services in Neenah, WI, said that counseling is generally the way to go, but that he'd be concerned if numerous complaints about the work environment cropped up. In that case, he said, he'd notify the patient's supervisor.

"No supervisor should tolerate the productivity poison of an unhealthy workplace, physical or mental," he declares. "This takes tact and skillful diplomacy on the doctor's part, but many times, everybody is better off if these issues are addressed openly. People need to be respected and listened to. If you have a supervisor who doesn't do these things, he or she is not the leader the company wants.

"Employers often contract with mental health agencies to give employees the proper resources for dealing with mental health issues. These agencies can hold group and team-building sessions that improve the workplace environment. They can also educate employees on how to confidentially access mental health resources."