Article

Should your CEO be an outsider or hired from within?

Groups are notorious for not grooming their doctors to be leaders. Why do so many prefer to hire strangers?

Group Practice Economics

Should your CEO be an outsider or hired from within?

Groups are notorious for not grooming their doctors tobe leaders. Why do so many prefer to hire strangers?

By Anita J. Slomski, Group Practice Editor

The recruiter, trying to find a physician CEO for a 30-doctor group,reads the job description. Not only must the doctor be experienced in qualityimprovement, provider profiling, and benchmarking, he also has to be a "magnetto physicians," charismatic, strong-willed, creative, and possess theall-important vision and sense of humor. "The group is basically askingfor someone who walks on water," says Jennifer R. Grebenschikoff, vicepresident of Physician Executive Management Center, a search firm in Tampa."But CEOs who lead groups today have to have this stuff."

Water-walking and charisma don't come cheap, however. This group plansto offer the ideal candidate a base salary in the middle to high $200,000s,plus incentives and a generous benefits package. The search is being drivenby the group's owner, a hospital that expects the new CEO to keep the group'sdoctors on board and stanch revenue losses.

Going outside the group to find a physician leader is a relatively newphenomenon. Not long ago, the top doc was generally a gray-haired old-timerwho presided over board meetings until another senior doctor got coercedinto doing the job. And the medical director--if the group had one--wasn'tchosen for his management acumen, either. "We used to take the guyswho were old, sick, or incapacitated--doctors who could no longer treatpatients, in other words--and make them our medical directors," saysendocrinologist Dale Lehmann, former CEO of Trover Clinic in Madisonville,KY. "That attitude is gone; we look for the best people now."

But as groups compete in an increasingly complex health care market,the best people to guide them may not be insiders who happen to have a bentfor business. A new breed, the professional physician executive, has emerged,and groups, hospitals, and managed care organizations are hiring them strictlyfor their management expertise. Generically speaking, their duties soundsurprisingly similar to those of corporate executives: strategic planning,mergers and expansion, contract relations, and uncovering new business opportunities.

Hiring an outsider to do the tough stuff

New Hampshire's Dartmouth-Hitchcock Clinic recently recruited three medicaldirectors for its southern region, which is composed of four multispecialtygroup sites of about 45 physicians each. "We were in an intense transitionto managed care, we needed leadership, and we needed it now," saysinternist Carl DeMatteo, southern regional medical director. One of thenew medical directors came from Kaiser and brought experience in utilizationmanagement, contracting with managed care, credentialing, and National Committeefor Quality Assurance accreditation. According to DeMatteo, "No onein our organization could have put together a medical management structurelike she did."

Groups facing productivity problems or divisiveness among the doctorsmay also look to an outsider to clean house. They want someone who hasn'tcurried favor--or lost credibility--with certain factions of the group,who won't refuse to fire Dr. Joe because they've played golf together foryears. "There may be qualified leaders within the group, but if they'vebuilt up too much political baggage over the years, they won't be effectiveat making changes," says pediatrician George Linney, a recruiter forthe search firm Tyler & Company. "No one is mad at an outsiderthe first day he starts work." That generally comes later.

At the 73-physician Springer Clinic in Tulsa, OK, animosity between primarycare physicians and specialists made choosing a medical director from amongthe ranks impossible. "Primary care doctors didn't trust specialiststo lead the group and vice versa," says internist Mark Sears, a veteranof the group who has acted as interim medical director for the last yearand a half. Sears succeeded two outside medical directors, each of whomlasted about a year.

Today there is more harmony at Springer, and Sears wants to return tofull-time practice. He thinks an inside doctor could handle the job, butthe group is again looking outside. "I can think of a few doctors herewho might be qualified, but no one has stepped forward," he says. "Insome ways, this is a thankless job. It's a big commitment of time, and alot of decisions are neither popular nor fun to make."

In many cases, a group looking for a full-time leader needs exactly that--toughdecision-making. "If a group agrees to pay a lot of money to a physicianCEO or medical director, it wants that person to be a change agent,"says recruiter Linney, a former medical director himself. "These groupsknow they have to do something drastically different from what they've beendoing. They're either in trouble or heading for trouble if they don't change."In other words, they're dissatisfied with the status quo, and eager to restructure,refocus, restrategize, re-energize--tasks often more easily accomplishedby an outsider.

When FP Roger Howe came to the 160-doctor Gould Medical Group in Modesto,CA, as vice president of medical affairs two years ago, the group had nosystematic way of determining when to add more doctors, and its subjectivecompensation formula meant that some doctors were overpaid while othersgot shortchanged.

Drawing on his medical management degree and medical director experience,Howe showed the group how to determine specialty staffing by the size ofpatient population--not by how loudly doctors complained about being overworked.He also took the data used to calculate physician compensation and "createdscattergrams and drew regression lines" to come up with a more rationaland objective formula. "The compensation committee then knew who wasbeing overcompensated, and some physicians had to take steep pay cuts,"says Howe. "They're still with the group, though."

That's not always the case. A new leader may cause an exodus of the rankand file. Although FP Keith E. Argenbright says he's most proud of making17 merged practices feel like a unified group of 35 primary care physicians,some doctors bolted during the transition.

Two and a half years ago, when Argenbright became medical director ofAll Saints Medical Associates in Fort Worth, and vice president of the hospitalthat owns the group, he jettisoned a policy that called for unanimous approvalof all decisions. "Groups fail when everyone has to agree," hesays. "So I instituted a democratic procedure where we would carryout the decisions of the majority. Those in the minority may not like thedecisions, but I expect them to go along with the rest of the group. A fewphysicians left because of that change."

Lest groups think an outside CEO is the answer to all problems, DaleLehmann is the first to tell them otherwise. Lehmann brought 22 years ofmedical administrative experience when he became CEO of the 100-doctor TroverClinic. A foundation had just acquired Trover, and the doctors were miserableabout being employees and their declining incomes. He was able to make somechanges, such as stabilizing income, but he candidly admits to not accomplishingwhat he set out to do.

"For ego reasons, a CEO may think he can do the job, but there'sa big difference between leading a solid group that's simply strugglingwith a changing marketplace and leading an operation that needs to be reorganized,"Lehmann says. Trover Clinic is part of a rural delivery system, and makingthe clinic's tertiary care services economically feasible in an area witha shrinking population had him stumped. After some 30 months, he left.

Would an insider have had a better chance? Trover is hoping so. Its newCEO is a pediatrician who had practiced at the group before leaving to getadministrative experience. Lehmann says his replacement is a good choice--witha shorter learning curve.

Pediatrician Karen Sterling, an executive Lehmann recruited to Trover,acknowledges the "extremely powerful" potential of internal leaders,but also touts outsiders' fresh ideas and objective perspectives. "Newblood challenges the mentality of 'this is the way we've always done it,'" she says. "If you have a mix of leaders from inside and outside,you have a stronger group."

But will they stay until tomorrow?

Although outsiders arrive with a mantle of neutrality, they may findthemselves skirting roadblocks set by the other physicians. "An insiderwho assumes the CEO position already has a certain stature within the group,"says the Gould Group's Roger Howe. "Physicians will grant outsidersa brief honeymoon--about four months--which is usually followed by a periodof organizational dissonance when it's almost impossible for the CEO toaccomplish anything. It took eight months before physicians decided I wouldstick around for a while and that maybe they'd listen to me after all. Thedegree to which I was tested by individuals was roughly proportional tohow long the physician had been with the group."

Mark Sears says he was given more leeway to make decisions as interimmedical director than his predecessors from the outside because the physiciansknew and trusted him. "I wasn't challenged on as many things,"he says.

The difficulty of wresting authority from the old guard is a key reasonwhy outsiders usually keep an eye on the door. "The average longevityof an outside physician executive is less than five years," says Howe."The rate of burnout is relatively high because medical groups expectadministrators who don't see patients to work very long hours. And the riskof a physician executive's leaving is even higher if he doesn't have a pre-existingcommitment to the group. So if he's working 16-hour days and someone offershim more money, he'll move."

Springer Clinic offers outside physician executives an accelerated partnershipshare in the group, but if the individual isn't committed to living in Tulsaor doesn't have a practice there, the expectation is that he'll leave intwo or three years. "It's just not realistic to think they'll stay,"Sears says. Adds cardiologist Mary Frances Lyons, a recruiter with Witt/Kiefferin Oak Brook, IL: "An outside person is likely on a career trajectory.Not many physician executives think of a 50-doctor group as the pinnacleof their success. Most are on their way to someplace else."

Some professional physician executives simply like the challenge of fixingtroubled groups, says pediatrician Roger Rathert, director of Cejka HealthcareExecutive Search Services: "They want the chance to solve problemsand add to their reputations."

Take a hard look in your own backyard

"Don't arbitrarily pass over your own physicians," says DeMatteoof Dartmouth-Hitchcock. "Before retaining a recruiter to find a physicianleader, always give insiders first crack at the position. Even if an insiderisn't selected, giving them due consideration neutralizes a potentiallydamaging issue."

To entice insiders to at least consider applying for a leadership job,Springer's Mark Sears recommends allowing them to switch back to full-timepractice in the event of an ill-suited match. "That way the personwon't get hurt too badly if things don't work out," he says. The fallbackoption can also produce a stronger leader. "If the group wants to fireme as medical director, I still have my practice to turn to," saysSears. "Therefore, I have fewer fears about the repercussions of myactions as medical director than an outsider would have."

Ex-Trover boss Leh-mann, himself an outside recruit, believes it's usuallybetter for a group to cultivate physician leaders from inside. "It'stragic that a big group can't develop its own physician leaders," hesays. "But when things are going bad, groups look at insiders and say,'You've been with us all along and we're still screwing up.' The problemis that groups don't want to train doctors in management because it takesaway from their productivity. But if doctors are going to run group practices,developing leadership skills is so important."

A recruiter can help--even if an internal candidate looks like a goodbet for the job. That way, the insider can be exposed to the same scrutinyas external applicants, thus satisfying group members that the home-growncandidate has the best credentials. "When things get tough, no onecan say that the inside doctor got the job simply because he was a convenientchoice," says recruiter Lyons. Expect to pay the search firm's fee--abouta third of the candidate's first-year salary--even if you choose the insider.

Fortunately for groups that choose to go outside to find a leader, thetalent pool of physician executives is relatively full. Currently, the AmericanCollege of Physician Executives has about 14,000 members working as medicalmanagers. Groups are asking for--and getting--doctors with five to 10 years'clinical experience, plus management skills specifically honed in grouppractices rather than in hospitals or HMOs.

"An MBA is desirable, but not mandatory," says recruiter Linney."In another five years, however, a management degree will be more importantfor candidates to have." According to a 1997 survey by Cejka &Company, a health care consulting and search firm, and the American Collegeof Physician Executives, only 22 percent of physician executives have postgraduatebusiness degrees, but the better-educated candidates command up to 20 percentmore in salary.

Unlike managed care organizations, where primary care doctors dominatethe corner offices, multispecialty groups are more interested in qualificationsthan in specialty. Applicants for executive positions are more likely tobe primary care doctors, however, since a $250,000 salary looks better toan FP than to an orthopedist. "And primary care doctors tend to havebetter political skills than specialists," says Linney. "Theyjust get along with people."

How much does leadership cost?

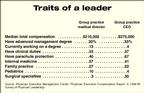

According to a Medical Group Management Association survey based on 1998data, the median total compensation for physician CEOs in all organizationswas $259,231; for medical directors, $160,000. In multispecialty group practices,physician CEOs earned a median salary of $220,000 in groups of 50 or fewerdoctors, and $282,562 in larger groups. Medical directors made $136,987in small groups, and $182,126 in practices of more than 50 doctors.

Another survey, by Physician Executive Management Center, found thatCEOs of group practices are the highest earners (a median of $275,000),followed by medical managers of integrated health care systems ($221,400),senior medical managers of group practices ($210,000), vice presidents ofmedical affairs and medical directors in hospitals ($196,710), and executivesin managed care organizations ($190,400).

Should your physician leaders be full-time administrators? Or shouldthey continue to see patients, and thereby generate revenue to offset someof their own cost? The answer depends on your group's philosophy. At Dartmouth-HitchcockClinic, for example, medical directors are required to practice at leastone day a week. Medical directors who have some clinical duties report morejob satisfaction, 20 percent more pay--and more stress than those who don'tpractice medicine, according to the Physician Executive Management Centersurvey.

Deciding when your group needs a full-time physician leader is a functionof size, and of internal and market challenges. A group of 50 definitelyneeds one full-time physician executive, say industry observers, and a smallergroup may benefit from a physician trained in business if it's trying tomanage risk contracts. "If you're a small group that just takes discountedfee for service, you don't need a whole lot of direction," says CarlDeMatteo.

Another option, of course, is to hire a nonphysician CEO to provide thebusiness and financial expertise your group needs--for considerably lessmoney. According to MGMA, nonphysician CEOs made a median salary of $110,000in 1998 in practices of 25 or fewer physicians, and $153,500 in larger practices.Springer Clinic has a lay CEO who will retire in a few years, and the groupis debating whether a physician should take his place. "Our currentCEO is a phenomenal negotiator, which is not something you learn in medicalschool," says medical director Sears.

Other groups, like the Scott & White Hospital and Clinic in Temple,TX, insist on having a physician in every key administrative role, preciselybecause doctors don't think like businesspeople. "Physicians give additionalweight in their decision-making to patients' best interests," sayspediatrician David Morehead, president of the Scott & White Health Plan."So having physicians in charge is essential for us."

Smaller groups may prefer a physician CEO who can be both a businessleader and medical director. "A nonphysician CEO does a lot of thingsa physician CEO does regarding the financial operations of the practice,"says Keith Argenbright of the 35-doctor All Saints Medical Associates. "ButI also view my role as setting strategy, doing one-on-one coaching of physicians,and disciplining and recruiting them. It's almost impossible to judge physiciantalent unless you're a physician."

Still, how do you know the money you spend on an unknown executive willyield a brilliant strategist and a respected leader? The short answer is,you don't. Hiring a physician executive is a lot like hiring a gastroenterologist:You can't really judge performance until you see her in action. "I'vedone a lot of interviewing and, at the end of the day, all you really knowabout a person is how he looks, how he talks, and that he doesn't throwfood around the table," says veteran physician CEO Lehmann. "Seriously."

Not even the candidate himself can be sure that he's the best personfor the job. "Even if he asks the right questions, he may not get accurateinformation because the doctors may not have a good feel for what's wrongwith the group," says Lehmann. Then again, giving management trainingto a promising insider may not pan out either. "You take a risk whenyou choose any leader for the group," says DeMatteo. "You canspend money training Dr. Joe, and find that he's not cut out for management."

In the final analysis, success is "dependent on the level of supportthe leader gets from his group," says Argenbright. "And the physicianexecutive must remember that he's working for the group and, therefore,must be subservient to the physicians."

That means rank and file doctors aren't excused from the hard work ofdeciding the group's direction. "Everyone has to get actively involvedin developing a strategic business plan or at least have a committee thatpresents it to the rest of the group," says Janice G. Cunningham, anattorney and consultant with The Health Care Group in Plymouth Meeting,PA. "The doctors can't just turn over their business to a CEO and thenbe nay-sayers. They have to continually monitor and evaluate the group'sprogress."

. Should your CEO be an outsider or hired from within?. Medical Economics 1999;22:88.