Article

Are you sorry you went into primary care?

That question on our Web page hit home. A surprising number of physicians answered with a resounding Yes.

WEB UPDATE

From our Web Poll

Are you sorry you went into primary care?

That question on our Web page hit home. A surprising number of physicians answered with a resounding Yes.

By Dorothy L. Pennachio

Senior Editor

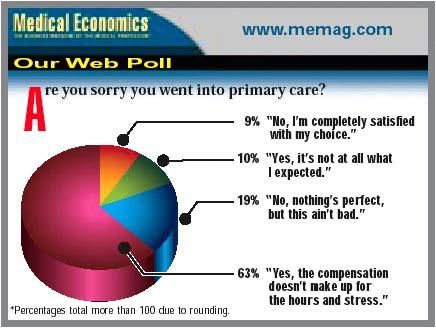

Today's residents are deserting primary care for more lucrative specialties and more desirable lifestyles, revealed our July 26 article, "Primary Care? Not me". But how do physicians who are already in primary care practice feel about their chosen field? To find out, we posted a question on our Web site asking readers whether they're sorry they went into primary care. Touch a nerve? Absolutely, we got more votes in that poll than in any we've ever run. You can see the results in the chart below.

Several physicians sent us e-mail messages elaborating on their votes. Rob Ferber of Seaford, DE, was the only correspondent to soften his Yes vote. Although he doesn't feel doctors are adequately paid for the long hours and stress of primary care, he does value the "appreciation he gets from his patients for making a positive impact on their lives."

"It was for that kind of compensation that I went into primary care," says Ferber. "But it sure would be nice to be paid in some reasonable proportion relative to my specialist colleagues."

Our other correspondents are having a hard time finding that one bright spot. One of them, John Elliott of Largo, FL worked as an ED physician for 14 years, then entered an FP residency hoping to change careers. Now he intends to return to the ED. "I made more money working 48-hour weeks as an ED physician than most primary care physicians working 80-hour weeks," says Elliott. He no longer sees a reason to consider primary care as a career. "Good luck, America!" he says. "In 20 years, there'll be few primary physicians left."

Cynthia Howard of Santa Fe, TX, is sorry she went into medicine at all. "By the time I finished my residency in 1998," says Howard, "medicine had totally changed. I grew up seeing the respect given to my pediatrician grandfather and his colleagues. It's not there anymore." Now, she says, specialist colleagues criticize her for even trying to assess patients before referring them, because she's "just a GP." And patients chide her for trying to get a $9.92 Medicare copayment, saying, "You already make a million dollars a year, so why do you need my money?"

"I just sacrificed my July paycheck to make a down payment on my malpractice insurance," laments Howard. "Where else but in medicine in 2002 can you find a job that has no vacation pay or sick time; no retirement benefits or health care coverage; and no certain paycheck? No wonder med school admissions are down. Kids today aren't that stupid!"

Stephen Zimmer of Murphy, NC, notes: "If you do this, you'll get sued; if you don't do this, you'll get sued." He's also tired of hearing "This isn't on my drug plan . . . I already know what's wrong with me . . . You'll need to call my insurance . . . My sister (uncle, brother, grandma) says you should send me to a specialist."

A Denver FP says, "Financial rewards in family medicine pale in comparison to other specialties. We FPs have not been a happy bunch essentially since medicine shifted from a fee-for-service to a managed care model. The idea of caring for patients from 'womb to tomb' is gonetoo many patients come and go as their insurance coverage changes."

"Declining reimbursements and increasing overhead costs have eliminated that wonderful comprehensive visit previously characteristic of primary care," he continues. "Instead, we have to glean little snippets of information about our patients along the way. And the added time and energy required to stay afloat often precludes us taking care of ourselves and our families."

He says none of his colleagues are happy, mainly because they can't do what they were trained to do.

"Dealing with HMO personnel who know nothing about the practice of medicine is wearying at best," he says. "There is less and less fulfillment from patient care as we race faster and faster just to stay afloat. Our specialty, very noble in its philosophy and intent, and once a vital part of medicine, is now a dinosaur. No wonder residency slots go unfilled."

Michael Gentile has been in primary care in Nutley, NJ, for 16 years. "Would I do it again?" he writes. "Not in this lifetime." Noting that he was writing to us at 7:30 pm after an exhausting day, he says, "I got up early to do rounds, then finished my charts and medical records. After lunch I saw patients in my office, then I answered a mountain of phone calls from patients, their families, a hospice, nursing homes, and hospitals. Then I went over the day sheet to see why it didn't balance. Now I have to get the bills mailed out so I can make payroll. When I add up all my work hours and divide them by the money I clear, I appear to be eligible for state aid.

"My staff wants to know why I don't have a summer house or a pool," he says. "The dermatologist or urologist they used to work for had one. I just hope to make enough to pay the electric bill so I can keep the lights on tonight while I finish my paperwork."

Dorothy Pennachio. Are you sorry you went into primary care?. Medical Economics 2002;18:31.